Optimising Africa's Use of Public Cloud Infrastructure

Author: Oguntayo Dipo

May 2024

The Public Cloud Landscape

Organisations’ use of public clouds has skyrocketed in the last few years, with businesses of all sizes leveraging the cloud and its benefits.

AAG’s Cloud Computing Statistics reports that in 2022, 60% of corporate data was stored in the cloud, a significant increase from 30% in 2015. This figure is expected to rise as cloud adoption becomes more widespread. In just seven years, the share of data in the cloud has doubled, showing the increased reliance on cloud technology in the business world.

Public cloud providers, also known as Cloud Service Providers (CSP), operate the infrastructure required to offer these cloud services. These providers make computing power, networks, storage, and databases available to customers worldwide, all delivered over the Internet.

According to Statista, the top three players, Amazon Web Services (AWS), Microsoft Azure, and Google Cloud, account for 67% of the total cloud market share in Q1 2024 (AWS 31%, Azure 25%, and Google Cloud 11%).

Each provider has established data centres in multiple geographical regions worldwide to provide resilient service and ensure customers choose the best location for their services near their users.

So far in the cloud story, Africa has also provided a market for these cloud services, although a small share. As of 2018, AAG reports that less than 1% of global public cloud spend was generated in Africa. However, the opportunity for growth is present with the same report stating, “Enterprise and wholesale markets on the continent are worth more than $10 billion, with over 400 companies generating more than $50 million in annual sales.”

Cloud Service Provider Infrastructure

a. Regions, Zones and Africa

CSPs organise their cloud infrastructure into cloud regions to achieve global reach and make services available worldwide.

Each cloud region comprises two or more Availability Zones (AZ), representing one or more isolated data centres hosting the hardware required for their services within the region.

This design ensures resilience within each region, as each AZ is independent. There is a reduced risk of a single event, such as a power outage or natural disaster, affecting all AZs in the region.

Despite this worldwide adoption of cloud services, there is very little footprint of CSP infrastructure in Africa. Among the top 3 cloud providers, AWS, Microsoft Azure, and Google, there is a combined presence of 4 Regions in Africa, all concentrated in South Africa.

-

AWS: AWS has 33 regions worldwide, with 1 in Cape Town launched in 2020.

-

Microsoft: Microsoft has 60+ regions, with 2 in Africa located in Johannesburg and Cape Town launched in 2019

-

Google: GCP has 40 regions in 200+ countries and has a single region in Africa, the Johannesburg cloud region launched in January 2024

b. Why Regions in Africa Matter.

CSPs can provide services worldwide without a presence in every country, so why is having multiple regions in Africa essential?

Two reasons why CSP customers want a region as close to their end-users as possible are discussed below.

i. Latency: Users have a better experience when their location is as close as possible to the cloud infrastructure serving them. This is because the geographical proximity results in reduced latency. Accessing servers in the same country or continent within a few milliseconds will yield better results than travelling hundreds of milliseconds or seconds between continents to access services.

The experience of playing a game, using an enterprise application, or loading audiovisual content is greatly improved with reduced latency.

Therefore, CSPs are incentivised to ensure their infrastructure is available close to customers with the shortest traffic path. Accessing a service in Africa will have a fraction of the latency compared to accessing the same service in Europe, America, or Asia.

ii. Data localisation and residency requirements: Data localisation or residency laws affect how data is collected, stored, processed, and transferred.

Data residency laws are concerned with the physical storage location of data. This refers to the actual geographical location of the servers and other infrastructure that are used to store and process data. These laws dictate that data must be stored within a specific country or region, often to ensure compliance with local data protection regulations.

Data localisation is the action of complying with data residency requirements. It is the practice of keeping data within the region from which it originated.

These laws require that data about citizens or residents of a country are collected, processed, or stored within that country before being transferred overseas. Typically, the data can only be transferred after meeting local privacy or data protection laws, such as informing users how the information is used and obtaining their consent. In some cases, the conditions that need to be met for data transfer are stringent enough to dissuade transferring the data.

Data residency laws and regulations are more stringent for different data types and industries. For example, health, financial, and government data are usually more strictly regulated.

Two primary drivers of data localisation and data residency laws are data security and data privacy. By keeping sensitive data within the borders of a particular country or a specified region, for example, in Africa, organisations handling the data can be subject to privacy laws and regulations. Also, it is essential to the security of this data if sensitive information is not transferred to other jurisdictions.

Other factors that drive data localisation and residency laws are economic considerations. Forcing organisations to store and process data locally will require them to build and maintain local infrastructure, thereby contributing to the local economy and creating jobs.

Having the regions located in South Africa will help CSPs satisfy data localisation requirements for South African entities and other entities that require data not to be transferred out of Africa. However, it will not help meet the data residency requirements for other African countries, which requires an increased number of regions on the continent.

Africa’s Internet Traffic Routes and CSPs

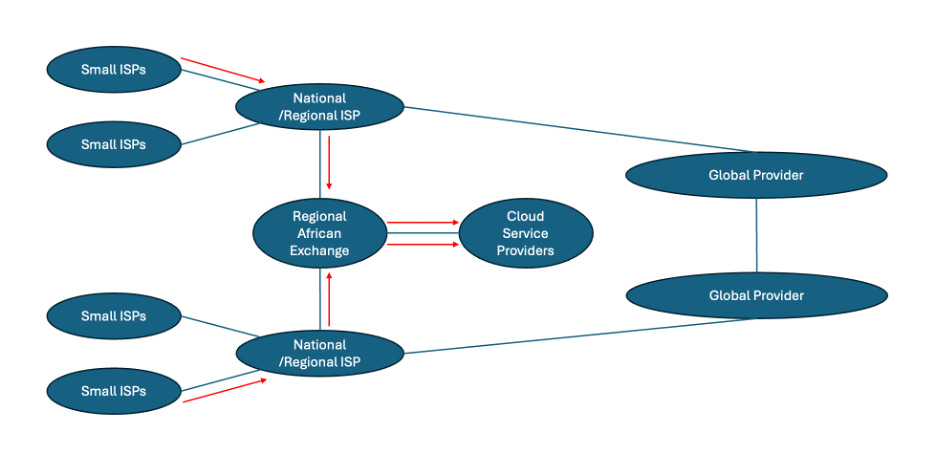

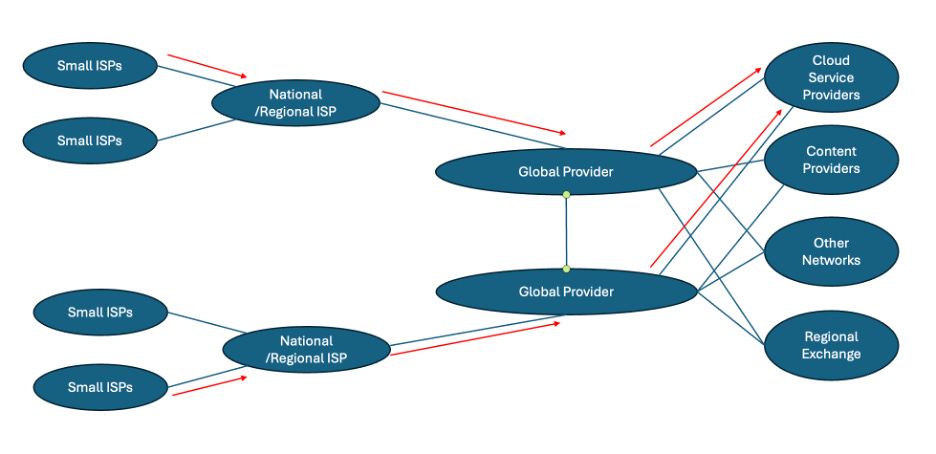

The diagram above illustrates the typical relationship between the ISPs in Africa, CSPs and the Global providers that connect them to destinations their customers want to reach.

Because most of the Internet traffic generated by African users is directed outside the continent, Internet traffic connections have been optimised for traffic leaving the continent rather than for other African countries.

National or regional ISPs pass their customers’ traffic and the traffic of other small ISPs that buy Internet Transit service from them to Global Tier 1 providers, usually in Europe, through submarine cable connections.

These Global Tier 1 providers are large networks that build and own extensive infrastructure spanning multiple countries. They can access the entire Internet and do not buy Internet transit from any other provider to reach any Internet location. In areas where they don’t have infrastructure, they peer with other Tier-1 networks to get free access to their network.

These Global providers include Level 3, Tata Communications, AT&T, and Zayo Group.

Buying Internet Transit from these Global providers is suited for global destinations. However, this arrangement is unsuitable for traffic bound to remain on the continent or be exchanged with other countries, like traffic to the CSP regions in Africa.

Due to the placement of these CSPs in South Africa, the typical traffic flow would for example be:

Nigeria (originating ISP) –> United Kingdom (Global Provider) –> South Africa (CSP)

Optimising Africa’s traffic routes to CSPs

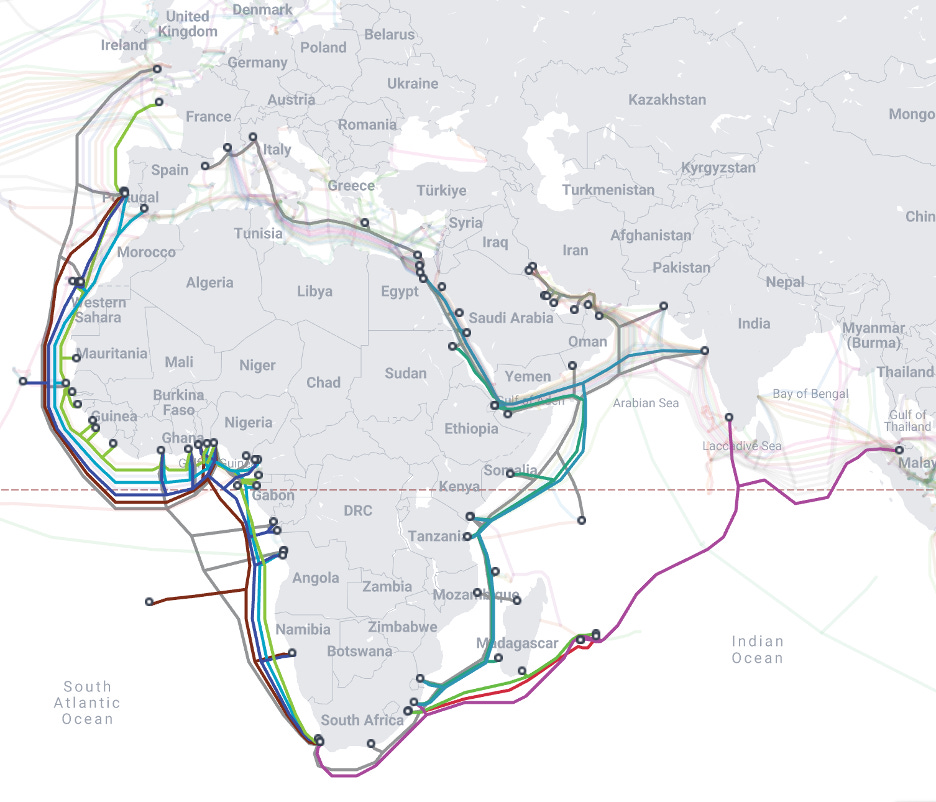

Two criteria must be met to provide better communication routing between users in other African countries and the CSPs regions in South Africa. They are Submarine fibre cable connection and Internet Transit or Peering arrangement.

a. Submarine cable connecting to South Africa.

Africa is served by several submarine cables, usually with multiple branching units that connect the cable to countries on its path. These branching units allow traffic to be inserted into the cable and transmitted to other branching units.

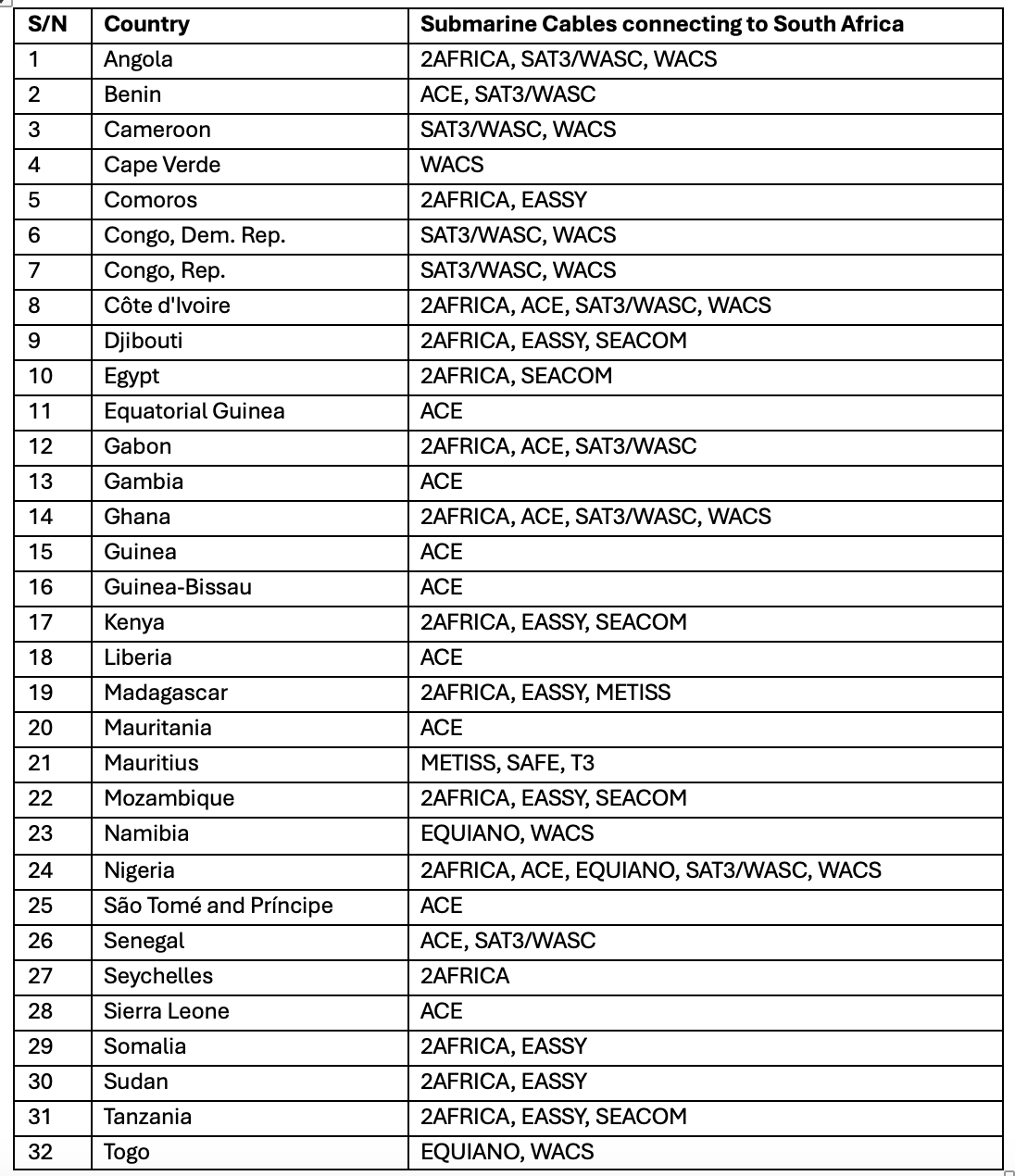

Currently, 32 of the 54 African countries have the potential for direct connection to South Africa via submarine cable. However, 22 African countries do not have access to any submarine cable capable of this direct connectivity.

16 African countries are landlocked; therefore, connection from these countries will require terrestrial fibre directly across to South Africa’s border countries or terrestrial fibre to other countries for access to their submarine cable infrastructure.

Below is a list of the countries that could connect directly to South Africa through existing submarine cable connections with branching units in both countries.

Source: Submarine Cable Map

Internet Transit or Peering

While submarine cables provide the physical infrastructure to connect other African countries to South Africa to exchange traffic with the CSPs, ISPs still need to come to peering or Internet Transit arrangements.

The different options are highlighted below:

a. Purchase Internet Transit from an ISP in South Africa connected to the CSPs: This arrangement will see providers from other parts of Africa establishing Internet Transit agreements with local Tier 1 ISPs in South Africa that are connected to one or more of the CSPs. The ISPs from other countries will hand their traffic over submarine cable to the local ISPs, who will deliver the traffic to the CSP. Unlike the peering options, this arrangement will involve paying for the Internet transit service to the local ISP to deliver this traffic.

b. Peer directly with the CSP: This arrangement is achieved through Private Network Interconnection (PNI), where the ISP connects directly with CSPs for settlement-free peering. In this scenario, the ISPs extend fibre to one or multiple locations designated by the CSP as peering points and send traffic destined for the CSP directly via this physical connection. While this might be the most direct means of connectivity, this type of peering will involve additional costs to extend infrastructure and doesn’t scale across multiple providers. The ISPs must directly connect to each CSP at multiple locations to ensure redundancy. There are also criteria that must be met, such as traffic volume, for the CSP to agree to peer with the ISP. In addition, direct peering will take more time to set up.

c. Peer with the CSPs at Internet Exchange Point (IXP): This arrangement is achieved through public peering. Public peering allows ISPs to connect with the CSPs, other ISPs and Content Providers over a shared fabric known as an Internet eXchange (IX). These IXPs are set up to facilitate traffic exchange and are usually a more cost-effective solution than having to peer directly with each provider.

The presence of the CSPs at the IXPs offers an opportunity for providers from all over the continent to establish direct connectivity by joining the IXPs and establishing settlement-free peering. This option is cheaper than the other two means of connectivity, and presence at the IXP helps the ISP reach the CSPs and other participants at the exchange point.

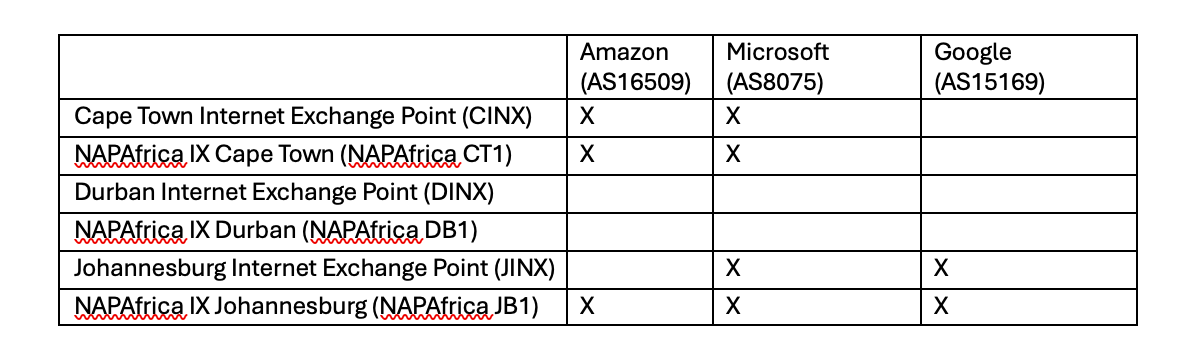

Below is a list of the IXPs in South Africa and the presence of the CSPs at the exchanges sourced from peeringdb.com.

Source: Peeringdb.com

The opportunity for IXP

ISPs with enterprise customers that have services deployed in the African regions need to provide their customers with the best routes to reach these CSPs. By advertising their ability to facilitate more efficient connections to CSPs, the IXPs in South Africa can attract these ISPs from all over Africa.

South Africa’s IXPs can also provide value-added services with the submarine cable providers and the CSPs to offer end-to-end connection services. This service will simplify the connection process for intending ISPs by bundling capacity on the submarine cable, the terrestrial connectivity to the IXP and the peering arrangement to the CSP into one easy-to-use service. This removes the complexity needed to set up these connections and attract potential connections.

This aggregation will, in turn, lead to the growth of the IXPs and provide an opportunity for South Africa’s IXPs to grow into crucial regional exchanges. Exchanges like the London Internet Exchange (LINX) and Amsterdam Internet Exchange (AMS-IX) serve similar purposes. This is an opportunity for Africa to grow an exchange to this scale.

Additionally, this aggregation of providers from all over Africa will promote better traffic exchange within the continent. Other traffic to private data centres and other African-hosted services will also benefit from having a direct path over the IXP infrastructure to reach destinations on other ISPs.

Initiatives such as the African Internet Exchange System (AXIS) Project have been launched to grow African IXPs into regional IXPs, but without the incentive for ISPs to connect and exchange traffic, these projects might struggle to achieve results. Investing in IXPs strategically located in relation to traffic destinations, such as CSPs and content providers, will help organically grow these IXPs and lead to better value for the money invested.

Part of the investment from these initiatives can also be channelled to subsidising the cost of purchasing connections on the submarine cables or terrestrial fibre required to reach the IXPs, which will be a significant cost for the connecting ISPs.

Below is an illustration of the potential optimised routing through the IXPs for traffic destined for these CSP regions in Africa.